Research in the field of behavioral economics has shown that people, as consumers, usually deviate from the model of consuming choices that maximize utility (Camerer, Loewenstein & Rabin, 2003).

However, having in mind that we might not always be rational when it comes to purchasing, do we manage to avoid marketing and shopping traps?

We all have been to the cinema. And even if we don’t have a clear preference between popcorn and nachos chips, we have certainly troubled our minds regarding the size that will better accompany us during the movie we are about to watch.

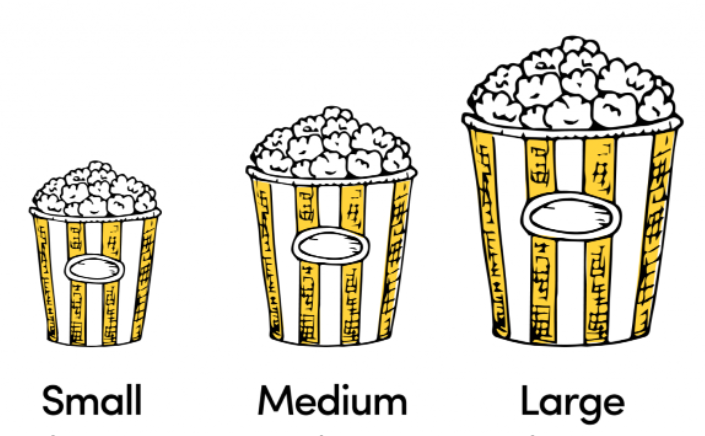

Let’s say that we face the two following options of pop corn:

- The Small size which costs 2.5€ and

- The Large one that we can buy for 6€.

Depending on our appetite, the choices overall will balance between the two options, or maybe slightly in favor of the Small size, since the cost of the Big size might be considered as too much by some consumers.

What do you think it would have happened if a third option of a Medium size was offered with a cost of 5.5€?

National Geographic conducted a relevant experiment where the choice of the Big size significantly increased after the introduction of a Medium size. With just half a euro extra we can enjoy a Big size popcorn even if we can not manage to eat it all. In other words, the “decoy” encouraged the consumers to choose the most expensive option. Relevant experiments, with the “trap” being a restaurant of medium fame, are demonstrated in the research of Huber, Payne και Puto who first introduced the concept of “decoy” in 1981.

The decoy effect (or trap or asymmetric choice) is the behavioral phenomenon according to which people change their preference between two options when a third one, not financially attractive, has been introduced (Bateman, Munro, & Poe, 2008). The evaluation of the significance of the effect has very much to do with the Reference Point theory which supports that consumers tend to evaluate the utility of a product/service not on the basis of its value but in comparison to the costs and benefits of other similar ones (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). In the case that the introduction of a decoy manages to significantly change the options of the consumers, then it highlights the fact that we indeed deviate from rational decision making.

It is important to mention, however, that the decoy effect has been recently criticized within the economists’ community as it is supported that the way options are presented to consumers may affect their future choices (framing effect) (Crosetto & Gaudeul, 2016). A “chicken burger” may be less attractive compared to a “Burger with Jack Daniels chicken fillet” (Wansink, 2001). Moreover, if the costs of the individual options are significantly different between each other, it might be the case that the decoy remains unnoticed. So, in the end, the question remains: do we “fall in the trap”? Do we buy what we need, what we desire or what the center of attraction is?

References

- Bateman, I. J., Munro, A., & Poe, G. L. (2008). Decoy effects in choice experiments and contingent valuation: Asymmetric dominance. Land Economics, 84(1), 115-127.

- Camerer, Colin F. & Loewenstein, George (2003). Behavioral economics: Past, present, future. In Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein and Matthew Rabin (eds.) Advances in

- Behavioral Economics (pp. 3-51). New York and Princeton: Russell Sage Foundation, Press and Princeton University Press.

- Crosetto Paolo, Gaudeul Alexia (2016). “A monetary measure of the strength and robustness of the attraction effect”. Economics Letters. 149: 38–43

- Joel Huber, John W. Payne, Chris Puto (1981). “Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: violations of regularity & the similarity hypothesis. Duke University

- Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), p.263.

- National Geographic, Brain Games S2E2

- Wansink, B. (2001). Descriptive menu labels’ effect on sales. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 42(6), pp.68-72.